BACKGROUND

The origins of curanderismo are an ever-evolving and complex hybrid of European influences and ancient indigenous cultural medicinal practices. This blend began to take place in the 16th century when Spanish Colonizers brought with them Greek, Roman and Arabic knowledge and theory of medicine to an already advanced Aztec civilization of the New World (Pabón, 2007. p.259).

Because the Spanish Conquest was rooted in violence and totality, it is unclear exactly how much indigenous healing lore has survived directly (Hendrikson, 2014. p. 78). What is known is that the pre-Colonial Aztecs were already practicing many healing techniques within their advanced system of socialized medicine.

The ancient civilization had a network of public hospitals and a vast centralized system of botanical research already in place by thee time the Spanish arrived in the Americas (Torres, 1983. p. 12). The famous Huaxtepec Garden was devoted entirely to the cultivation of medicinal herbs, and had a roughly seven mile circumference (Torres, 1983. p.13).

Elements of curanderismo thought to have been introduced by Spanish explorers include the use of the healing elements of chamomile, garlic, onions, rosemary, oranges and lemons (Torres, 1983. p.13). These natural elements are still found in many modern curanderismo rituals and prescriptions.

The resulting confluence was not a single model of health but a holistic practice of treating mind, body and spirit. When visiting a curandero, the patient is treated in regard to their internal imbalances as well as their relationship with nature and society. Over time thus re-conceptualizing health and the treatment of illness into a new form as the New World merged with the old (Coronado, 2005. p.165).

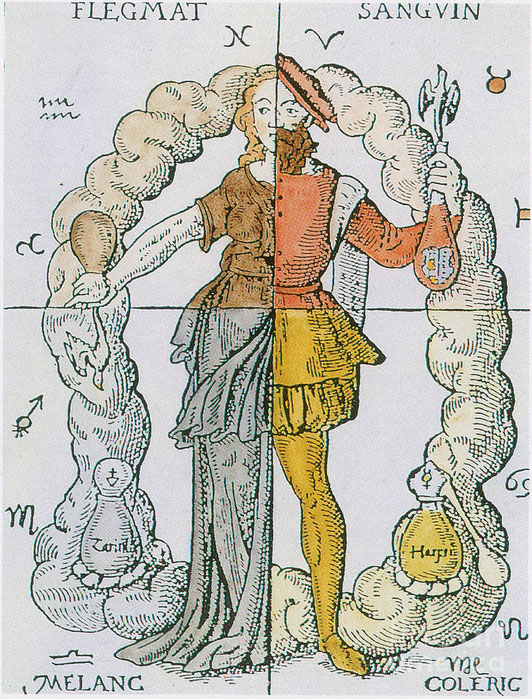

Perhaps of most consequence, however, was the introduction of the theory of the four humors of the body (blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile). This theory claims that all disease comes from an imbalance of one of these elements, came from Greek physician and “Father of Medicine” Hippocrates II (Torres, 1983. p.14.). In addition to bringing with them the “modern medicine” of the 16th century, the Spanish also brought with them the Roman Catholic Church whose influence on curanderismo is still prevalent today.

The influence of the Catholic Church on curanderismo is perhaps the most complicated. The Roman Catholic Church of the 16th century and beyond brought with them wealth and power as well as the violent methods of forced conversion to the Americas (Hendrickson, 2014. p. 76). Much of what may have existed at the core of curanderismo in indigenous culture- absent Catholic influence- has all but been wiped out since their arrival. What exists today in practice maintains a strong veneer of Roman Catholic symbols and materials.

Materials commonly used and associated with Roman Catholic tradition include: eggs, lamb, olives and olive oil, candles, perfumes and essential oils, crosses, holy water and pictures of religious figures and saints (Salazar, 2013).

Although most modern practices incorporate these religious material symbols and saints, many within the Catholic Church actually reject curanderismo as a form of brujera or black magic that is contrary to Church doctrine (Salazar, 2013) and look upon it with much skepticism. However, this is a complete misconception as a curandero (male) or curandera (female) by definition is said to only process el don ("the gift") and their abilities to heal through the divine power of God (Salazar, 2013).

A part of the misconception has to do with the conjuring of dead spirits used within many rituals of the curandero (Salazar, 2013), and the use of religious symbols may have actually evolved as a way to placate both the church and its converts. Many curanderos themselves believe that these items are not of any actual importance beyond helping to relieve the stress of the patient and putting their mind at ease, with prayer itself being sufficient for healing (Salazar, 2013).

Resources Cited:

Coronado, Gabriela. "Competing Health Models in Mexico: An Ideological Dialogue between Indian and Hegemonic Views." Anthropology & Medicine12.2 (2005): 165-77. Web.

Hendrickson, Brett. "Restoring the People: Reclaiming Indigenous Spirituality in Contemporary Curanderismo." Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality 14.1 (2014): 76-83. Web.

Pabón, Melissa. "The Representation of Curanderismo in Selected Mexican American Works." Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 6.3 (2007): 257-71. Web.

Salazar, Cindy Lynn, and Jeff Levin. "Religious Features of Curanderismo Training and Practice." Explore (New York, N.Y.) 9.3 (2013): 150-158. Web.

Torres, Eliseo. Green Medicine: Traditional Mexican-American Herbal Remedies (1983). Web.