CURANDEROS AND CURANDERAS

Within the practice of curanderismo, it is just as common to find male healers, known as curanderos, as it is to find female ones, known as curanderas (Torres, 1983. p. 8). Each healer is said to possess el don ("the gift") of healing, which is given to them by God. There is often an “origin story” of sorts with each individual curandero and in which they discover their own abilities through witnessing a miracle or by being noticed or healed themselves by an existing curandero or curandera (Salazar, 2013).

Even though el don is considered an inherent quality, one does not become a curandero simply by being blessed. There is much training that must occur first. Likewise, simply possessing el don and not honing one's abilities is considered very dangerous among the practice. This is because the person with "the gift" is said to have been blessed with a mind capable of being influenced by the spirit world, making them vulnerable to demonic possession if they are not armed with the ability to protect themselves (Salazar, 2013).

Desarollo, or the training in curanderismo is an arduous process (Salazar, 2013). Desarollo typically takes place under the direct tutelage of a curandero or curandera and takes on average four of five years to complete (Coronado, 2005. p. 170). Although material lore such as books exist, most of what is taught within desarollo is passed on directly through the oral tradition (Salazar, 2013).

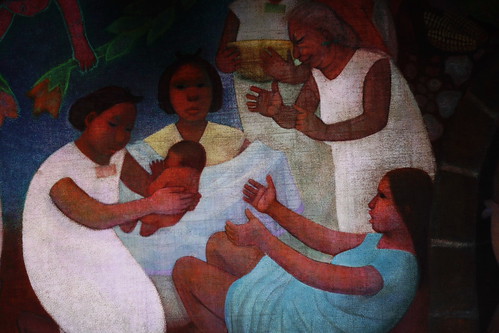

Within the frame of curanderismo there are different types of practitioners, similar to how within Western medicine there are different medical degrees and specialists. These classifications include: yerberos or herbalists, sobadores or masseuses, espiritualosos or psychics, senores or tarot card readers, parteras or midwives and hueseros or bone-setters (Salazar, 2013).

For the curandero, sickness or disorder is believed to have a duality of natural and supernatural causes. Natural causes include: germs, genetics, psychological forces and dietary habits (Salazar, 2013). Supernatural causes include elements from the spirit world as well as external curses and hexes that may have been placed on the patient, with or without their knowledge (Salazar, 2013).

Curanderos operate within three different levels of healing: the material (nivel material), the spiritual (nivel espiritual) and the mental (nivel mental) and this is often related to their specialty (Pabón, 2005). The material level includes midwifery, herbal treatments, folk massage, and remedios caseros, or home remedies (Pabón, 2005). The spiritual level involves the contacting of the spirit realm and is often done through an altered state of consciousness where the practitioner allows other spirits to enter their body as a medium (Pabón, 2005).

The mental level is the psychic approach which can be done at a distance and involves the healer's ability to channel psychic mental vibrations towards the patient's ailment (Pabón, 2005). The majority of modern curanderismo is done at the material level, although some curanderos are well versed in all three levels of healing. The mental level is said to be the hardest and rarest among curanderos as training is exhaustive and rigorous (Salazar, 2013).

Resources Cited:

Coronado, Gabriela. "Competing Health Models in Mexico: An Ideological Dialogue between Indian and Hegemonic Views." Anthropology & Medicine12.2 (2005): 165-77. Web.

Pabón, Melissa. "The Representation of Curanderismo in Selected Mexican American Works." Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 6.3 (2007): 257-71. Web.

Salazar, Cindy Lynn, and Jeff Levin. "Religious Features of Curanderismo Training and Practice." Explore (New York, N.Y.) 9.3 (2013): 150-158. Web.