METHODOLOGY AND RITUALS

The first basic core belief within curanderismo is the power of God to heal, “based on a balanced state of being that was also in balance with the environment in both spiritual and physical terms” (Pabón, 2005). The second core belief is in the medicinal powers of plants and animals to heal, which is thought to be largely based on indigenous views and folklore (Pabón, 2005).

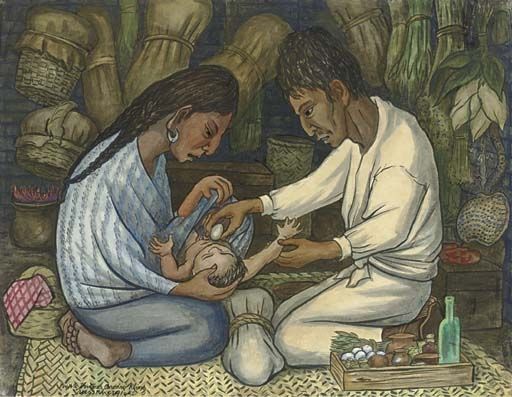

These two core beliefs are acted out by each individual curandero and demonstrated within the performace of each treatment in a ritual form (Sims and Stephens, 2011. p. 99). In this context, curanderos are always performing a sacred ritual that is based in divination, but not one that is overtly religious (Sims and Stephens, 2011. p. 106).

While the overwhelming majority of curanderos are practicing Catholics, the person receiving the treatment can be inside or outside the faith and denomination (Salazar, 2013). The context of this co-mingling is rooted in the historic forced conversions of the Roman Catholic Church of the Spanish Empire (Hendrickson, 2014. p.78).

Anecdotal evidence has shown that belief in the treatment on behalf of the person receiving it is not necessarily a prerequisite for its effectiveness (Salazar, 2013). In fact, many people have visited a curandero and been treated of their ailments only to remain wary and suspicious of the practice.

This is likely because many rituals of the curandero have been stigmatized over the years as either "evil or silly" (Coronado, 2005. p. 167). Younger and more urbanized people may also see the practice as antiquated and lacking in scientific basis.

Within curanderismo folklore, it is said that the spirit acts as a “guardian of an individual's mental health,” and if the spirit fails to do so the soul is greatly affected leading to dysfunctions caused by an excess of rage, envy or sadness (Salazar, 2013).

Thus, the patient is not blamed for their illness but rather it is seen as an “attack” (Salazar, 2013). Many ailments are thought to be caused by imbalances in the four humors or calidades (qualities) of the boy: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. Each humor or quality of the body is said to have an inherent "state" of balance and therefore imbalances are treated with inherently “hot” or “cold” remedies to regain equilibrium (Salazar, 2013).

Some of the most common treatments involve some form of “cleansing” of the body, home and soul of spirits by performing a limpiada espiritual (Salazar, 2013). Therapeutic touch, faith exercises and the conjuring and exorcising of spirits and demons are also common elements of ritual treatments. Roman Catholic symbols and saints are often used directly or indirectly (Salazar, 2013).

The performance of many ritual treatments have a designated beginning, middle and end to them. For example, the treatment for mal ojo or "evil eye" typically involves the passing of a whole raw egg in the shell over the inflicted individual to remove the negative energy. The egg shell is then cracked open into a glass and if it forms an “eye” shape the person is said to be healed of the malady (Macko, 2014). This is an example of a “sweeping” cleanse ritual, known as a barrida (Hoogasian, 2010. p. 302).

Occasionally modern ritual practices even invoke the names of Aztec gods and spirits such as Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, and Huitzilopochtli as a way to remain more connected to tradition (Henrickson, 2014. p. 77). Some of these modern methods invoke both pre-colonial and post-colonial lore simultaneously, while others choose to reject anything related to Roman Catholic orthodoxy for the purposes of indigenous cultural reclamation (Hendrickson, 2014. p. 82).

Since so little remains of specific Aztec lore in relation to the folklore of curanderismo, practitioners who take this approach are viewing the culture and tradition of curanderismo in a naturalistic way (Handler and Linnekin, 1984. p. 273). By directly incorporating Aztec deities and beliefs, they are attempting to meld the old and the new as well as the modern.

Resources Cited:

Handler, Richard, and Jocelyn Linnekin. "Tradition, Genuine or Spurious." The Journal of American Folklore 97.385 (1984): 273-90. Web.

Hendrickson, Brett. "Restoring the People: Reclaiming Indigenous Spirituality in Contemporary Curanderismo." Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality 14.1 (2014): 76-83. Web.

Hoogasian, Rachel, and Ruth Lijtmaer. "Integrating Curanderismo into Counselling and Psychotherapy." Counselling Psychology Quarterly 23.3 (2010): 297-307. Web.

Macko, Haley. “Evil Eye in the Mexican and Central American Culture.” ANP 204: Introduction to Medical Anthropology (Summer 2014), 15 July 2014, anthropology.msu.edu/anp204-us14/2014/07/14/evil-eye-in-the- mexican-and-central-american-culture/.

Pabón, Melissa. "The Representation of Curanderismo in Selected Mexican American Works." Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 6.3 (2007): 257-71. Web.

Salazar, Cindy Lynn, and Jeff Levin. "Religious Features of Curanderismo Training and Practice." Explore (New York, N.Y.) 9.3 (2013): 150-158. Web.

Sims, Martha C., and Martine Stephens. Living Folklore: an Introduction to the Study of People and Their Traditions. Utah State University Press, 2011.