MODERN PRACTICE

The use of traditional Mexican folk medicine within Mexico and among Mexican-Americans has been reported to be as high as 50 to 75% in some areas (Hoogasian, 2010. p. 299) and the reasons for this are multifaceted. Often people seek the services of a curandero as a last resort, once all other available resources have been exhausted.

In one survey of people who used curanderismo, many respondents just "wanted help with the problems of life and took comfort in the personalized attention and holistic approach taken for their problem" that is often found to be lacking in modern Western medicine (Salazar, 2013).

Many patients use curanderismo because of its close proximity and because the local curandero will speak the same language. Others cite barriers to access of modern medicine that might exist because of poverty, oppression or legal status (Hoogasian, 2010. p. 298).

Often the visit to your local curandero is much more affordable than mainstream medicine- or even free- as many practitioners refuse to accept payment beyond small donations for subsistence (Salazar, 2013). An additional benefit are the relatively safety and low occurrence of side effects inherent to modern curanderismo methods.

Some practitioners make use of curanderismo as a way to stay connected to their pre-Colonial past, even as there is more of a push to embrace universal healing and wellness for all people (Hendrickson, 2014. p. 76). Much of this movement is focused on a reclaiming of Mesoamerican indigenous tradition, often at the exclusion of Spanish, European and Roman Catholic influences (Hendrickson, 2014. p. 78).

One such course, "Traditional Medicine Without Borders: Curanderismo in the Southwest and Mexico" is taught by Eliseo “Cheo” Torres and offered during the summer at the University of New Mexico (Salazar, 2013).

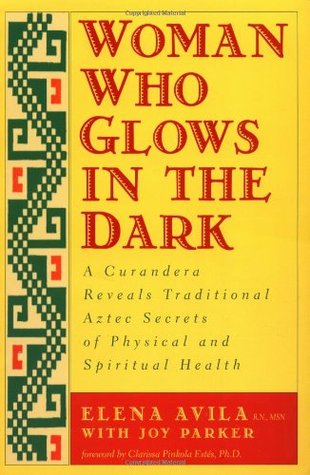

One famous modern curandera who focused on indigenous interpretations of the folklore was Elena Avila (1944-2011). Avila wrote the book Woman Who Glows in the Dark: A Curandera Reveals Traditional Aztec Secrets of Physical and Spiritual Health (Hendrickson, 2014. p. 79). Her work and others like it see curanderismo as a “developing spirituality” seeking to reclaim and integrate Indian heritage into modern identity (Hendrickson, 2014. p. 80).

Even though most modern curanderos are members of the Catholic Church, they often do not wear this affiliation on their sleeve. There are many mixed feelings on the subject, due to the long-standing Christian identity of curanderismo and its ties to the colonial era and racism (Hendrickson, 2014. p. 77). Others see curanderismo not as a separate clandestine religion, but as “a logical extension of popular Catholicism” (Hendrickson, 2014. p. 80).

Resources Cited:

Hendrickson, Brett. "Restoring the People: Reclaiming Indigenous Spirituality in Contemporary Curanderismo." Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality 14.1 (2014): 76-83. Web.

Hoogasian, Rachel, and Ruth Lijtmaer. "Integrating Curanderismo into Counselling and Psychotherapy." Counselling Psychology Quarterly 23.3 (2010): 297-307. Web.

Salazar, Cindy Lynn, and Jeff Levin. "Religious Features of Curanderismo Training and Practice." Explore (New York, N.Y.) 9.3 (2013): 150-158. Web.